A few days after their capture at Kalamata, more than 5000 prisoners-of-war, Kevin among them, were entrained and sent to an abandoned army camp in Corinth. They remained there for up to six weeks while the ever-efficient Germans were putting into place a plan that would transport 1,000 POWs a day to Stalag 18A. At 3 o'clock on the morning of June 6, Kevin was put aboard one of the first of those trains although at the time he had no idea of his destination.

Braillos Pass

From Kevin's memoir:

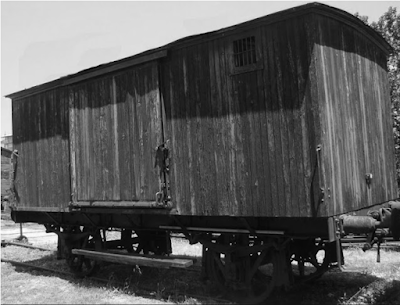

The train was on a narrow-gauge line, 40 men to a wagon, 35 inside and a five on the roof. I had suffered badly from dysentery in the Corinth camp and I desperately wanted to get away from Greece. On this day I got my wish. We were marched to the railway station. We had not even left the station yards when I realised this was not going to be the Orient Express.

We arrived at Grevia at 3AM and were herded off the train. We were then marched 40 kms over the [5000 ft] Braillos Pass to a rail head near the town of Lamia. With the arrival of dawn, the day grew hot.

The hot weather, powder dust and lack of water made it a very tough day. The lentil soup diet at Corinth was not coping with our physical needs either. The guards also felt the heat and they became prickly and unpredictable. Escape became the focus of my thoughts. Then I realized that my emotions were getting the better of me particularly when I noticed that the guards were accompanied by Doberman and Alsatian dogs.

I recognised a bloke who came from Benalla, (nicknamed) Possum Bill. He was with Tom Laracy, from Barnawartha. These two were older than most of us. They saw that I was in distress, so they helped me reorganise my pack. They gave me the encouragement I needed to keep on going.

When we arrived at the rail head, a standard gauge train was waiting to take us the rest of the way. Possum Bill walked up to the locomotive. He opened his pack and pulled out some tea leaves. With a wink he told me to sit tight and went ahead to open a valve. Steam gushed out and he filled his mug with boiling water and made a brew. He generously shared his tea with me and Tom. After this I began to recover.

Possum Bill knew all about trains. He worked with Victorian Railways before and after the war. In 1960 we lived in Wangaratta. The Melbourne-Albury railway line ran behind our back fence. A new standard gauge Melbourne-Sydney line was being constructed parallel to the existing broad-gauge line. One day Kevin heard a familiar whistle. He looked over the fence and a rail track worker waved to him. It was Possum Bill with his trademark grin.

G’day Kev, ‘ow ya goin’ mate?

Footnotes: Kevin told me Possum Bill's real name when he told me this story however it has since escaped my memory.

Kevin was raised on a farm near Wangaratta, in central Victoria. Of the two towns mentioned, Benalla lies 42 km to the south-west and Barnawartha, 48 km to the north-east.

Tom Laracy

Private Tom Laracy served with the 2/17 Battalion in North Africa, Service No. VX11733, POW No. 4001. Remnants of this battalion were transferred to the 6th Division and sent to Greece. Tom was one of them. He was captured in Kalamata, Greece on 29 Apr 1941.

Tom's record on the AWM website states that he was born at Rushworth, Victoria on 14 Jun 1907. If the photo of Tom at the Klagenfurt camp were taken in, say, 1943, Tom would have been about 36.

While researching this article, I discovered that Tom died in 1986 in Beechworth, a town not too distant from Barnawartha. The Barnawartha Cemetery has a commemorative plaque for Tom and his wife, Marie. It shows that Tom was not born in 1906 but in 1899. This being the case, the above photo is of Tom aged 44. He was about 87 when he died. Tom obviously put his age back seven years in his bid to enlist. A relative told me that Tom put his age up to enlist in WW1 but his uncles dragged him out of the line.

The Braillos Tunnels

Quote from Lt Ron Lister's 1993 memoir:

Some engineers from Melbourne did most of the damage, blowing bridges over sheer drops into gorges, bringing down whole sections of roads on steep mountainsides, with the final touch of loading railway trucks with explosives and time fuses and sending them on their way into the numerous railway tunnels on the Braillos Pass itself. …enough time had been gained to allow the main body of troops to get away by ship and the demolitions held back for three days any advance by German vehicles.

The Numbers

In April 1941, the Churchill government sent more than 62,000 troops to Greece to defend its ally from the German invasion. Of these, 22% became prisoners-of-war. Source: Long, Gavin, Greece, Crete, and Syria, 1953. Collins.

For further background reading, try the Australian War Memorial’s article.

My father, Kevin Byrne (1918-2006), was an Australian prisoner-of-war of the Germans in WW2. 'In the bag' was the expression he used to describe this unfortunate period of his life. This blog is intended to invoke the memory of the POWs in Stalag 18A work camp located in Klagenfurt, Austria.

Friday, 26 June 2020

Tea? Anyone?

Friday, 19 June 2020

Mick Cister

Michael Ralph Cister, Mick, was born

in Cape Town, South Africa on 2 Mar 1924. In 1941, Mick was a 17-year-old

galley boy aboard the British merchant ship, Eleonora Maersk. This

vessel was commanded to stand off Crete to evacuate Allied soldiers.

Unfortunately, it was sunk by a German submarine.

Mick managed to survive the sinking.

Despite his civilian status, he was made a prisoner of war and

incarcerated in Stalag 18A and sent to the Klagenfurt work camp. Mick was

the youngest in the Camp by almost three years. As you can see in this photo below, he

was just a lad. But he was not only the youngest, he was the first in the

Camp to die.

|

| Hut Group. Mick Cister is on the extreme right of the photo |

On 16 Jan 1944, Mick was on a work party

clearing snow on the Lend Canal. The canal, located near the centre of

Klagenfurt, was used by the locals for recreational skating. On that day, the

RAF targeted Klagenfurt for its first bomb raid. Although the raid focused on

the rail yards, a rogue bomb hit the work party. Andreas Sihler, a guard

was killed as were several French POWs. Mick Cister, along with another

Australian POW was wounded.

Mick, however, never recovered from his injuries. He died 21 days after the incident, on 6 Feb 1944. He was buried in the Klagenfurt War Cemetery. Contrary to the age shown on his headstone, Mick died 24 days short of his 20th birthday.

|

| Mick, mid-1943, now 19, sitting on the step with shirt sleeves rolled up. He was killed six months after this photo was taken. |

Saturday, 13 June 2020

Walter Tollinger

On 4 December 1939, while drinking in a bar in the presence of army personnel, he announced that "the German war in Poland is a swinishness and Hitler is a blackguard and a criminal as well!" This statement, and other information in this article, was taken from the book, Sentenced to Death – Nazi-Justice and Resistance in Carinthia.

The word 'swinishness' could probably be substituted by 'pig-headedness.' Although Tollinger was arrested for his public criticism of Hitler, his punishment was not severe.

In 1944, Walter Tollinger resumed his public criticism of Hitler. On 4 April 1944, after voicing his contempt of the German campaigns in Russia, a sergeant who had been fighting on the Russian front, answered: "coming back home as a wounded man, I have to meet such a swine as you. I won't accept to sacrifice myself for persons like you!" The sergeant then asked Tollinger to go with him to the Gestapo headquarters and challenged him to repeat his remarks. Perhaps Tollinger misjudged the seriousness of the situation – or was intoxicated. In any event, he accepted the challenge, and the Gestapo placed him under arrest. Tollinger was sent for trial on 11 November 1944, charged with "undermining military morale." He was found guilty and received the death penalty. On 8 December 1944, along with eight others charged with similar crimes, Walter Tollinger was executed by firing squad.

|

| A Tollinger portrait of my father, Kevin Byrne. In the photo below the Tollinger brand is shown on the reverse side (although it is upside down). |

Friday, 5 June 2020

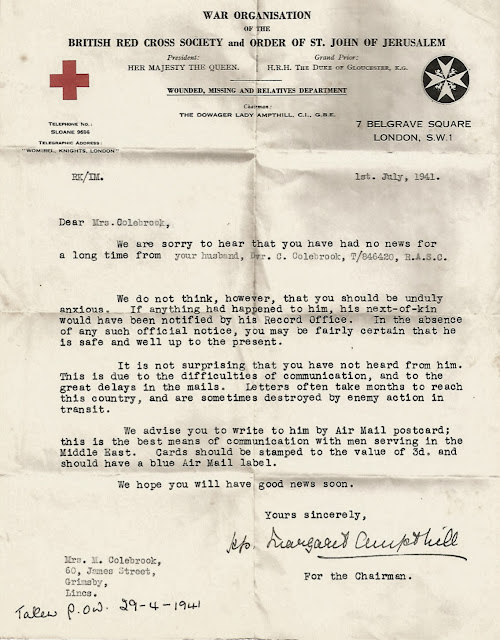

Dixie Colebrook

Charlie, by then a driver with the Royal Army Service Corps, soon found himself in Greece. His diary shows that he was captured at Kalamata on 29 Apr 1941; he arrived at Corinth on 6 May; at Salonika on 13 June; at Wolfsberg on 2 July, and at Klagenfurt on 25 July.

After his discharge in 1946, Charlie joined the Police. He spent 30 years as a PC before retiring in 1976. Charley died from a heart attack in 1982 aged 61.

Post Scripts

When en route to Dunkirk riding in the back of an army truck, a Panzer tank appeared out of cover and Charlie’s truck stopped suddenly, with everyone jumping out quickly. That is, all except Charlie. He was carrying the squad's Bren Gun and its barrel became caught in the camouflage netting. While trying to release it, the German tank got closer. The hatch popped up, and the tank commander stared straight at him, observing Charlie’s plight. Charlie gave him a stifled grin as he freed the gun. They both nodded at each other. With his weapon now disentangled, Charlie jumped off the truck and ran for cover. At that point, Charlie could hear and see the tank’s machine gun following his flight with a trail of bullets. The tank commander was laughing as he did it. A story of compassion for an enemy, I think.

Late in the war, while on a work detail near Klagenfurt, Charlie was riding on the back of a truck. A fighter aircraft flew low to strafe the truck. The vehicle braked so suddenly that Charlie was thrown over the top and landed on his face, taking off part of his nose and some of his ear. Taken to hospital, the doctors performed plastic surgery to repair his face.

|

| Charlie and Madge's Wedding, 1940 |

|

| Dixie with fellow POW, Ken Filmer |

|

| Dixie Colebrook, standing, left |

|

| The accommodations at 10029/GW were 16 to a 'hut.' The sergeant, front centre, is the only soldier of that rank in the camp. He was the camp's "Man of Confidence." Dixie is standing second from left. |

|

| Charlie is the taller of the two soldiers. 1945 |

|

| Charlie and Madge with daughter Susan, 1947 |

|

| PC Colebrook |

Letters and Documents

Kevin Byrne's Photo Collection

... with some others thrown in. Kevin meticulously wrote the names on the back of the photos. He got a few wrong, spelling-wise, and someto...

-

Even as a lad I wondered how my father was able to build a collection of photos taken while he was a prisoner-of-war. Some were obviously ta...

-

Arbeitskommando (work camp in English) 10029/GW, in the Klagenfurt suburb of Waidmannsdorf, held about 250 army 1 prisoners. The commandant...

-

... with some others thrown in. Kevin meticulously wrote the names on the back of the photos. He got a few wrong, spelling-wise, and someto...