Sundays were rest days. The mornings were devoted to

housekeeping and the afternoons to leisure. To keep themselves occupied

constructively, the MOC established committees to arrange sporting events,

especially in the warmer months. The events were often built around national

teams. Scotland, Wales, England, New Zealand, and Australia fought out battles

on both the football pitch and the cricket ‘oval.’ The annual athletic carnival

was called the Empire Games.

The POWs were paid 8 pfennigs a day for their labour - a

requirement of the Geneva Convention. Wages were sometimes pooled to buy

sporting equipment but by 1943, the Red Cross stepped up. Kevin’s photograph

collection featured several photos of sports games, all with players names

printed on the back.

Back: Lofty Windsor, Alan Eason, L Wood, C Morris, L Eliott,

Tiny Petersen, R Thorpe, W Cassidy. Front: G Conyard, G Nowells, M Thomas, S

Pendlebury, Bob Behen, H Lanham, Don Winter.

Aussie Tug o' War Team. 1944 Empire Games. Standing: Roy

Thorpe, Les Wood, ‘Tiny’ Petersen, ‘Lofty” Windsor, Sitting: Bill Cassidy, Jock

Nowell, Alan Eason, Mick Thomas, Les Eliott.

Stan Pendlebury (Australia) finishing first in the 75 yards

sprint. Aug 1944 Empire Games.

Australian footbal teamBack: John O’Malley, Lofty Windsor,

Rob Adams. Middle: George Richardson, Ted Bradburn, Alan Eason. Front: Eric

Green. 1943. Alan Eason and Eric Green were killed in the bomb raid on 19 Feb

1945.

Cricket Match Scorers, June1944. Back: Harry Mitchell

and ‘Dixie Colebrook Front: Bill Cassidy, Taffy Griffiths and Jock McGechie.

The Football Final drew a big crowd.

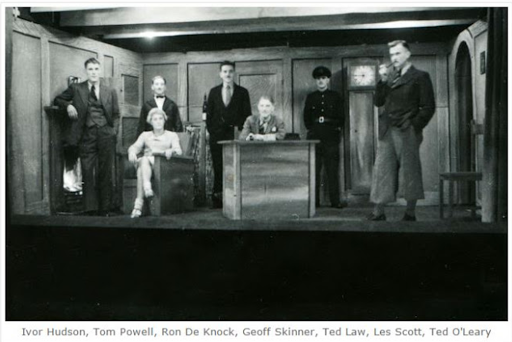

Not all were serious. "Our Girls" Football Team,

May 1943. Back: Leo Turton, Len Chadwick, John Dawson, Pat Kershaw, ‘Darkie’

Reynolds. Front: Ken Kewel, Don Michie.

Novelty Football Match. 26 Dec 1942. Australia vs Scotland.

Australia: A Anderson, AH Smith, F Welch, D Duggan, John Burrows, F Murray, J

Holman, Chas Lawrence, Scotland: R Porter, James Coid, J Whittet, Les Scott, W

Sutherland, Angus McDougall, A McNeill, Stan Summers. Johnny Dawson, GK Bisset.

C May (umpire).

Profiles

From the photos below …

Wilfred Angus Bailey

Gunner Wilfred 'Bill' Bailey was a member of 2/1 Field

Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery. He was born in Sydney on 23 Aug 1913 and

enlisted on 7 Nov 1939. Post-war, Wilfred lived in Caroona, in central New

South Wales. He retired to live in a war veterans home in Narrabeen. He died in

Sydney on 7 Oct 1983 aged 70.

Robert Bartlett

Private Robert 'Kinder' Bartlett was a member of 28 Maori

Battalion, New Zealand Infantry. Kinder played guitar in the camp orchestra.

William Jefferson Gilbert

Signalman William Jefferson Gilbert, Jeff, was a member of 1

Corps Sigs. Jeff was born in the Melbourne suburb of Northcote on 20 Aug 1919.

He was one of the six men killed bin the bomb raid on Sunday, 19 Feb 1945.

Christmas 1942: Back: Kevin Byrne, Jack Holman, ‘Scotty’

McLeod, ‘Jeff’ Gilbert, ‘Lofty’ Windsor. Front: Fred Payne, R. Bartlett,

Wilfred Bailey

John Holman

Private John 'Jack' Holman, 2/9 Battalion, lived in the

Melbourne suburb of Caulfield when he enlisted. Jack was born in Kent, England

on 21 Jan 1906. Post-war he was a butcher in the Melbourne suburb of East

Malvern. He died in Emerald, Victoria, in 1984, aged 78.

Alexander McLeod

Lance Corporal Alexander 'Scotty' McLeod was born 8 Jul 1908

in Glasgow, Scotland. He enlisted at Bondi, NSW in 1939. He was a member of the

Australian Army Service Corps. No post-war records have been located suggesting

that he might have remained in Britain after the war.

John Aubrey O'Malley

Private John O'Malley in the 2/11 Infantry Battalion. He was

born in Geraldton, Western Australia on 16 Jun 1916. He died there on the 10

Oct 1980 aged 64.

Frederick C. W. Payne

Driver Fred Payne, was a member of the Royal Army Service

Corps.

Edward Peake

Edward Peake, Ted, was a assigned at different times to both

10029/GW and to 11066/GW. Both work parties were in the Weidmannsdorf work camp

in Klagenfurt. Before the war, Ted lived at Dairy House Farm, Ashley, Cheshire.

John Ernest Warburton

Private John Warburton served in the 2/11 Infantry

Battalion. George was born in Brunswick Heads on 19 Apr 1915. Post-war, John

farmed at Wokalup, WA. John died in Bunbury, WA on 13 Dec 1989. He was 74.

James Alexander Windsor

Private James Windsor, Lofty, 2/11 Battalion, was born in

the Western Australian wheat-belt town of Northam on 30 Sep 1918. He was a

member of the 2/11 Battalion. James was captured in Crete. He was single when

he enlisted but married just before he embarked for the Middle East. James was

killed in a motor accident on 20 Dec 1947, less than two years are being

discharged from the army. He was 28. He left a wife and three children.

John O'Malley, Edward Peake and John Warburton, Jan 1942.

Kevin Byrne's Memoir - Part One

My army career began on August 5th, 1940 at the Caulfield

Racecourse where the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) had established a Recruit

Reception Centre. I had turned 21 the previous October and had been working for

almost six years in Oaklands, a small town in the New South Wales Riverina. I

was ready to move on. At Caulfield, we were kitted out with the basic

necessities and uniforms. We also got some basic instruction in marching and

parade drill.

This went on for three weeks after which we were sent to the Balcombe army camp

on the Mornington Peninsula for basic weapons training. We were also inoculated

in preparation for travelling overseas. In September, I was assigned to the

advance party of 30 men to go to the 2/23 Battalion, which was located at the

Albury Showground. Albury Grammar now occupies this site. The 2/23 was then

renamed the 2/23 Training Battalion.

In WW1, the Australian army was called the Australian Imperial Force – the AIF.

So when volunteers were called for to form a Division following the outbreak of

WW2, it was called the 2nd AIF. The Battalions that fought in WW1 such as the

23rd Battalion (Albury’s Own) were called the 2nd 23rd but written simply as

2/23.

While at Albury I contracted the mumps and spent six days in the Albury Base

Hospital then was given a week’s sick leave. My parents lived in nearby

Wangaratta, so I went home to convalesce. When I returned to Albury, I found

the camp almost deserted. The men formed the nucleus of the 2/29th Battalion

and finished up in the 8th Division in Singapore and Malaya and eventually

prisoners of war of the Japanese. The 70 or so men that remained in the camp –

most had just returned from leave like me – were invited to put their names

down for various units such as Signals, Engineers, Artillery, and Transport. I

loved motor vehicles and didn’t hesitate to nominate the Australian Army

Service Corps as a truck driver. My application was successful, and I was

posted to the AASC’s Moore Street depot in South Melbourne,just around the

corner from Victoria Barracks. I received driver training and got my army

driver’s licence. Over the next four weeks, I spent much of my time ferrying

new army trucks from the Ford Plant in Geelong to Port Melbourne from where they

would be shipped overseas.

In mid-December we were ‘invited’ to put our name down for

an overseas posting. I was out on a job at the time and later found that two of

my mates, Jack ‘Bluey’ O’Brien and George ‘Aspro’ Aspden both put my name down.

Bluey put it down for the 7th Division and Aspro for the 8th. The duplication

wasn’t picked up and my name was down for both the 7th and the 8th. In the end,

I was sent to neither. I was allocated to the 6th Division.

On December 20th, 1940, we were told we were going overseas and given 14 days

pre-embarkation leave. Bluey O’Brien married Nora O’Keefe at Dookie the next

day. I was best man. After spending Christmas with my family in Shepparton I

travelled to Oaklands for a ‘send-off’ by the local Returned and Services

League. A week or so after returning to South Melbourne, we were sent back to

the Balcombe camp to prepare for departure. The 6th Division was fighting in

North Africa, so I had a pretty good idea where we were heading. The Balcombe

camp was a rather pleasant place save for the actions of a sergeant who had it

in for me. He had wrongly accused me of being AWOL at South Melbourne and

wanted to charge me. I sought a redress and won the hearing but that made his

attitude towards me even worse.We completed our admin and wrote our Wills and

finally we were ready to depart.